As if life were not complicated enough there is another quality that is well worth knowing about and that is how transparent (or not) the paint is. This is particularly important when working with glazes where you want the base colour to show through. Clearly if you use a transparent colour on top, the base colour will show through to make an optical mix of both colours but if the top colour is quite opaque it will ‘bury’ the base layer. On the other hand if you want to ‘bury’ or heavily modify the base layer colour then using an almost opaque colour might help; though you might end up muddying the picture.

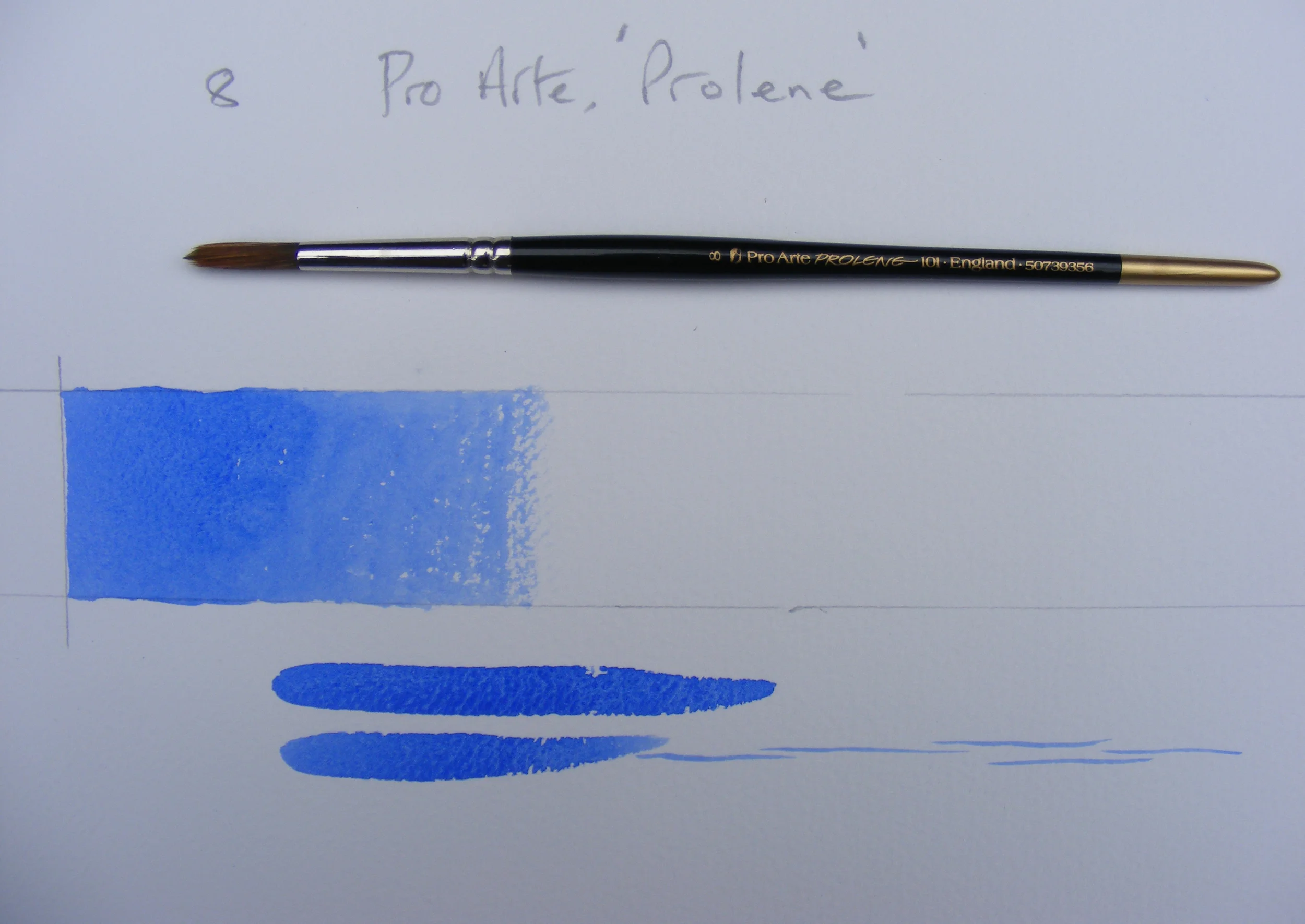

The test for this is very simple; all you need do is paint a strip of black acrylic paint on your paper and then paint the test colour over it, at right angles. If the paint is transparent it will hardly change the look of the black at all, whereas paints that are opaque leave a coloured chalky residue on top of the black which can be seen quite clearly (look at Cerulean in the blue set)

Have a look back at lesson 3 and you will see another reason why it matters. Watercolours ‘work’ because the light travels through the paint and bounces off the paper support and back to the viewer, this is what gives watercolours their unique quality of luminosity. If the paint is applied so that it is almost opaque, like gauche, it will stop the light getting to and from the paper thereby ‘deadening’ the colour. I am definitely not saying don’t use opaque colours just be aware that when used with too little water they will soon make your painting dull and muddy (which is fine if you want the dull and muddy look).

If we have a look at the blue set…

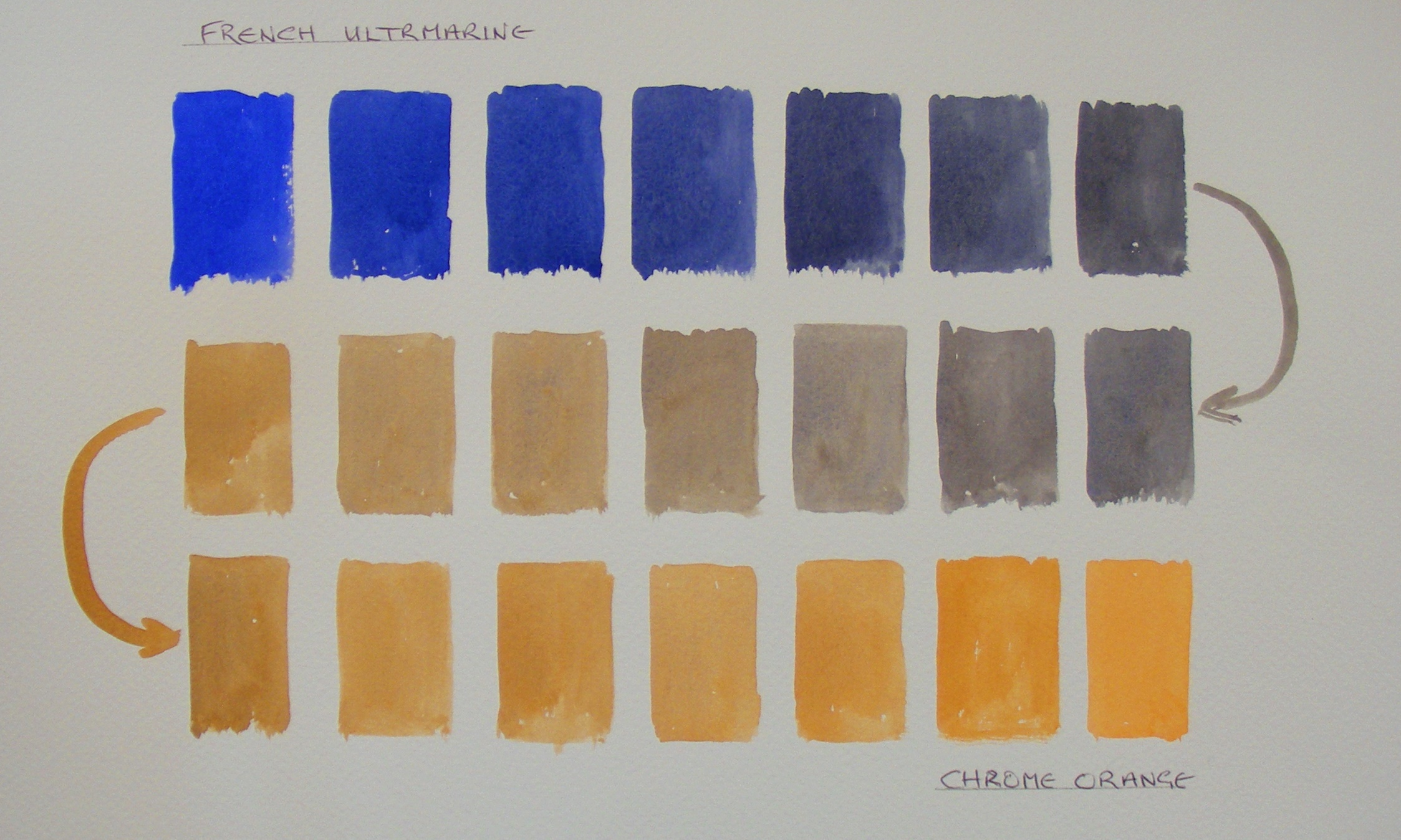

Cerulean Blue is clearly the most opaque colour and although it is difficult to see on the image, if you do the test yourself, you will see that French Ultramarine also leaves a slightly opaque layer over the black.

With the red set, it is quite clear that Cadmium Red is by far the most opaque, so although it looks a very bright red straight from the tube it will soon ‘deaden’ any mix, if used with too little water.

Winsor Red and Scarlet Lake are moderately opaque and all the other reds are virtually completely transparent.

In the green set it is Cobalt Turquoise that stands out as the most opaque. It is a colour that I find very useful when painting around the coast of Cornwall but I am always sure to use it with plenty of water to make sure it does not look ‘dead’ and chalky.

Viridian is not quite as opaque as Cobalt Turquoise but it comes a close second and Winsor Emerald is moderately opaque and all the others are virtually transparent and that is probably why Sap Green looks so vibrant.

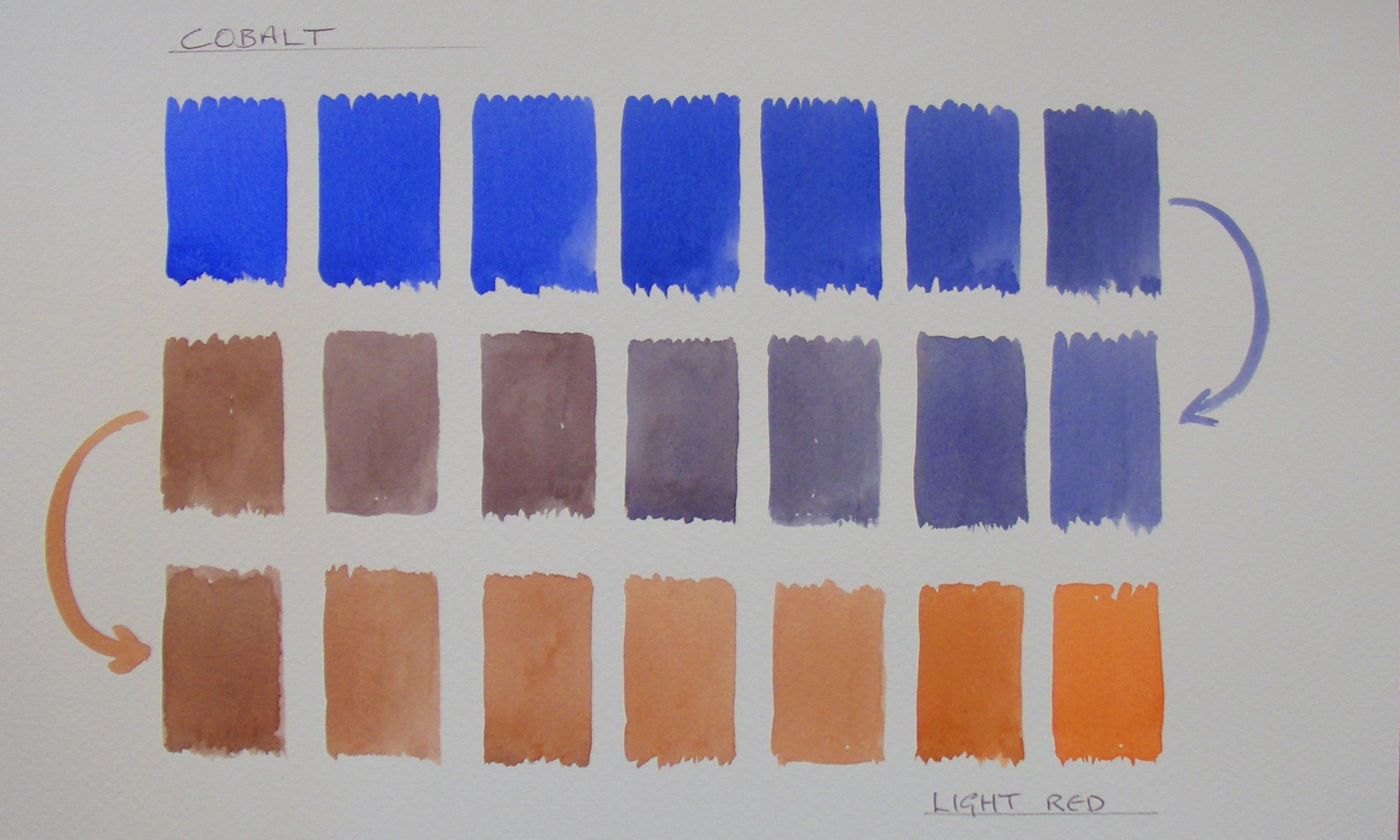

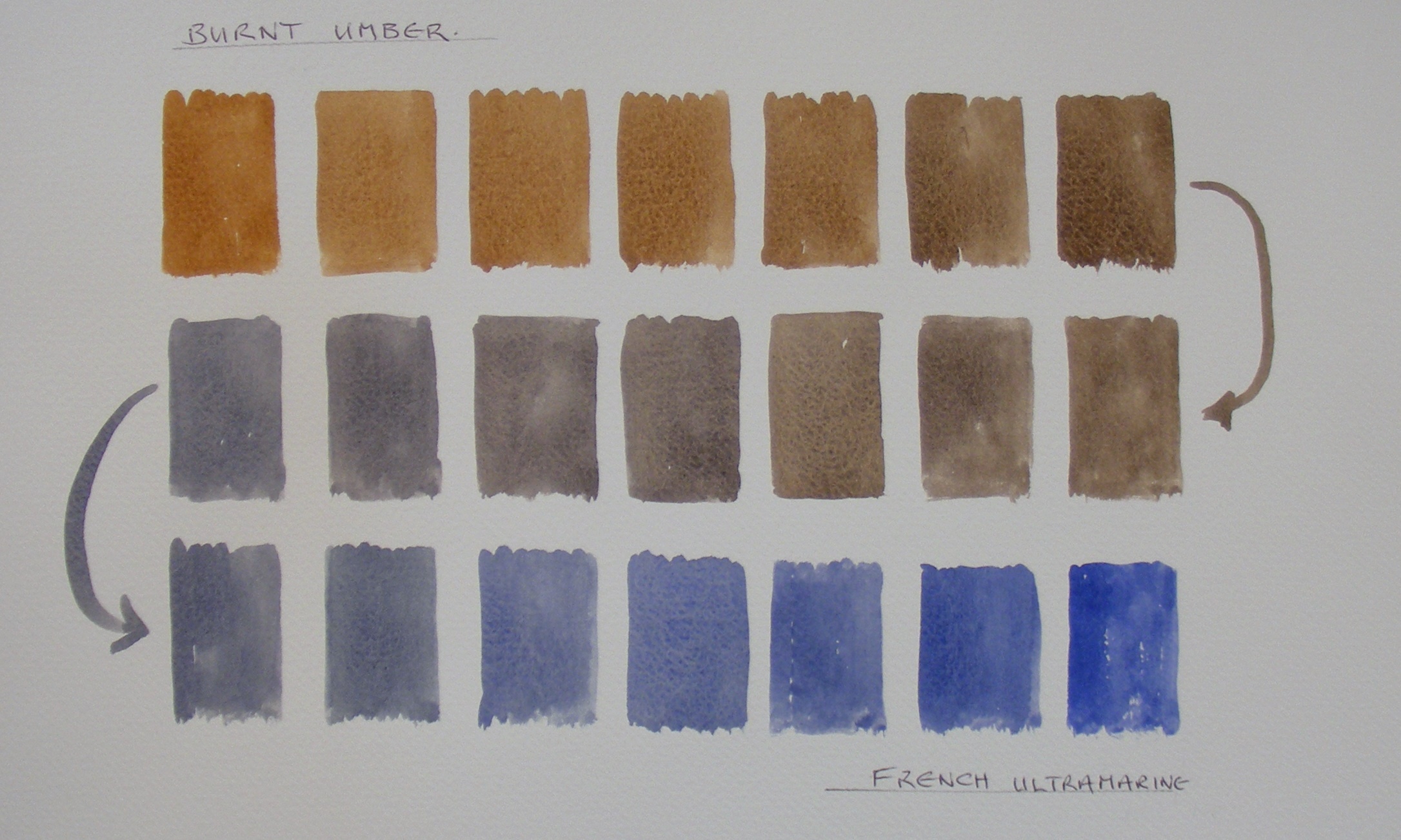

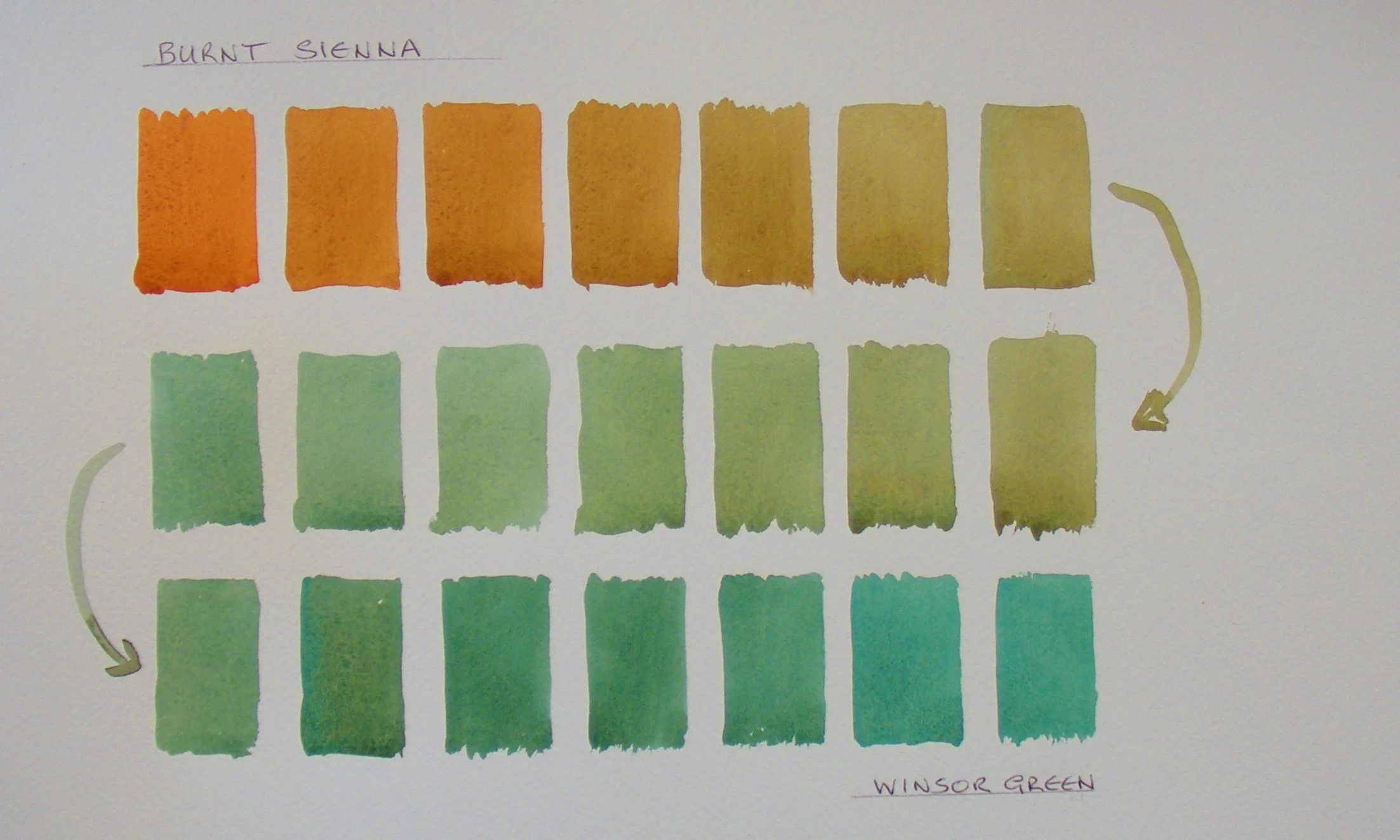

Although all these colours (or close equivalents) can be mixed from primaries, I find this group of tertiaries particularly useful for landscape painting; particularly when looking for a variety of greens. Subtly different greens and greys can be made by adding different blues to the tertiary colours, the variety of the resulting mixtures is enormous and once you learn to control these green mixes you will never be tempted to use Viridian straight from the tube again (or worse still Hookers Green).

By far the most opaque is Yellow Ochre followed by Gold Ochre and Raw Sienna. Yellow Ochre is however one of my most useful colours but it has to be used with plenty of water particularly in skies, otherwise instead of suggesting a warm evening light it slips into suggesting a sandstorm!

Burnt Umber Burnt Sienna and Raw Umber are moderately opaque, which is only to be expected as all these earth colours are formulated from ground up pigments. This is one of the reasons that pictures can soon become (literally) muddy looking if too little water is used when mixing with these colours.

With the yellow set, Cadmium Yellow Pale is the most opaque with Winsor Yellow Deep coming a close second. So although Cadmium Yellow Pale looks bright it can soon deaden when used in mixtures with too little water and for bright greens I would reach for New Gamboge instead; it looks very similar but being almost completely transparent it can be mixed without deadening the colour.

Naples Yellow is only moderately opaque but it is a colour I seldom use because it looks so ‘chalky’, being almost more like a white than a yellow and in case you haven’t noticed I never use Chinese White.

All the other yellows are virtually transparent and I use New Gamboge as my warm primary and Aureolin for my cool primary yellow. New Gamboge is a particularly powerful yellow and is very useful for strong green mixes. Aureolin is a very delicate colour but because it is completely transparent it can be very usefully employed for soft greens.

That just about wraps up this lesson on Transparency and Opacity. What I suggest you do, if you have any doubt about how a particular colour will behave on the paper, is to try it out on some scrap paper first.

The great challenge with watercolour, unlike oil, acrylic and pastel is that you only really get one crack at it. With the other mediums you can (more or less) wipe away or paint over a passage you are not happy with and modify the image; this just does not work with watercolour. Almost every mark you make will show in the final painting so it’s doubly important to be able to control and predict what will happen when the paint settles.

In lesson 9 we will have a look at how ‘powerful’ any particular colour is and I will show you an easy way of finding out for yourself before you end up chewing your elbows off in frustration and wishing you had never just ‘added a dab’ of a particular colour.